|

| "Women's Activities," Oregonian, April 19, 1922, 12. |

Monday, August 24, 2015

The Portland Branch of the Women's Overseas Service League Organized 1922, With Eleanor Ewing, R.N. as President

Women who served overseas in the First World War from Portland, including the women of Base Hospital 46, were eligible to join the new Portland Branch of the Women's Overseas Service League, organized on April 17, 1922.

The first president of the League was Base Hospital 46 nurse Eleanor Ewing.

Monday, August 17, 2015

Grace Phelps and Women Veterans: Some Men Were Nervous About an All Female Veteran Organization in Portland

Grace Phelps, who had served as chief nurse of Base Hospital 46 in France and then in the same capacity for Base Hospital 81 after the close of the war, was a leader of women veterans in Portland.

|

| Grace Phelps. from "Grace Phelps, R.N.: A Portrait in Sepia," online exhibit from the Historical Collections & Archives, OSHU http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/education/library/about/collections/historical-collections-archives/exhibits/grace-phelps.cfm |

In 1921, women organized a national Women's Overseas Service League to fulfill this need. Portland women, led by Grace Phelps, took steps to organize a local branch in the spring of 1922.

|

| "The Citizen Veteran," Oregonian, February 12, 1922, Section 2: 22. |

The column suggests that there were tensions and opposition from some male veterans about the formation of an all female group. "Most of the women who are back of the organization already are members of the American Legion, so it is not an attempt on their part to form a veteran organization not in harmony with those already in existence." Local American Legion leaders "declared that the clubrooms [of the Legion] should be thrown open to the women for their meetings."

Grace Phelps addressed the opposition head on: "We are not attempting to break away from the American Legion," she insisted. "With the nurses and other women war workers in an organization of their own we will probably be able to render valuable assistance to the legion."

The column listed those "aiding Miss Phelps in plans for the local organization" as Miss Jane Doyle, Miss Marjorie MacEwan, Miss Ann Steward and Mrs. Merle Campbell. More on these plans in the next posts.

Monday, August 10, 2015

Life After Base Hospital 46 Service in the First World War: Stasia Walsh Part IV

Base Hospital 46 Nurse Stasia Walsh, R. N., worked with the Red Cross in Serbia for four years after World War I. Her 1920 passport application provides some interesting clues about her status and service.

Walsh was an Irish national when she immigrated to the United States and studied nursing in Iowa and worked as a private duty nurse in Pendleton, Oregon. She served with Base Hospital 46 as an Irish citizen. And when the Red Cross called her for postwar duty in East Europe in early 1920 she became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

The first page of Walsh's 1920 passport application tells us that she became a naturalized U.S. citizen in Pendleton, Oregon on January 10, 1920. Her application was dated February 13, 1920. Nurses who served with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps during the war had to either be a citizen or "must before appointment make a declaration to become such, and, if she wishes to continue in the Nurse Corps must at the proper time take our final naturalization papers." (Stimson, Army Nurse Corps, 288). I'm trying to find out what the American Red Cross required for citizenship of its workers in the aftermath of World War I or whether this was Walsh's choice. The timing coincides with her application for and assignment to nursing in Poland and Serbia. Her passport application indicates that Walsh was still in the planning stages for her new employment -- she had not made her travel reservations (or the Red Cross had not yet made them for her). She also evidently hoped to travel back to her home in Ireland and to other European nations in addition to her work in Poland.

The second page of Walsh's passport application suggests that she was in a hurry -- instead of having the passport mailed to her in Pendleton she indicated that she would call for it, perhaps in Portland.

The Women's Overseas Service League bulletin Carry On, announced in February 1925 that Walsh had recently returned from four years of Red Cross service in Serbia. She was going to marry T. G. Dunn in March 1920 and would move with him to St. Anthony, Iowa. Marriage license records indicate that he was a 44 year old farmer. I would love to hear from Iowans or others who know more about her journey after her marriage.

Walsh was an Irish national when she immigrated to the United States and studied nursing in Iowa and worked as a private duty nurse in Pendleton, Oregon. She served with Base Hospital 46 as an Irish citizen. And when the Red Cross called her for postwar duty in East Europe in early 1920 she became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

| |

| Stasia Walsh, U.S. Passport Application 1920, p. 1, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, Ancestry.com |

|

| Stasia Walsh, U.S. Passport Application 1920, p. 2, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, Ancestry.com |

|

| "Miss Stasia Walsh," Carry On, 4, no. 1 (February 1925): 35. |

Monday, August 3, 2015

Life After Base Hospital 46 Service in the First World War: Stasia Walsh Part III

Stasia Walsh, R.N. who served on the nursing staff of Oregon's Base Hospital 46 in France during the First World War, returned to Umatilla to work with the Red Cross and identified as a veteran with the American Legion and Women's Overseas Service League. In February 1920 she received an assignment to go to Eastern Europe for service with the Red Cross in the aftermath of war, revolution, and refugee crises.

During the war, as we've seen, newspapers reprinted letters home from local women and men in service. And newspaper editors continued the practice as local residents continued overseas service. On May 1, 1920, the Pendleton East Oregonian reprinted a letter from Stasia Walsh that her "Pendleton friends" shared with the paper. Walsh reported that she was in Belgrade "placed in charge of a clinic for Serbian children and examines from 55 yo 80 children each day." The clinic brought a foreign aid worker like Walsh together with a young Serbian woman with little English and a Serbian who spoke only Serbian and a "Bulgarian prisoner of war" to administer the clinic for the children. Belgrade was a "queer mixture of East and West."

The Pendleton paper printed parts of another letter from Walsh, this one to Mrs. M. J Cronin, in December 1920. Walsh wrote that after she left Serbia she went to her native Ireland for two weeks. The country was in the midst of a war for independence with fierce fighting. Without giving specifics she felt that "it is a very sad country now. I hope that things will be brighter for them later on."

Walsh was now in Red Cross service in Poland, again an independent country after World War I but where there was still conflict on its borders. Walsh gave information about where to send mail and information about her travels. And she gave a brief but informative description of her living quarters in the city of Kracow. "There is an immense castle just across the street from us. We are living in an old monastery. It is a find bring building but cold as a barn and no coal to heat it. We have one room with a storve and we sit there and write, and so forth, during the day."

Walsh's letter also reported on local and US women whom she had see and met in her travels to Paris, Belgrade, and Kracow. Several women were from California "and the western states" and "a number of them have been to the Pendleton Round-Up." Pendleton was becoming famous for its early fall Round-Up, ten years old in 1920. It became one common touchstone for Americans abroad who had visited Pendleton's attraction and a point of pride for Pendletonians abroad and at home.

Walsh also told her friend that she had seen Eglantine Moussu "in Paris several times." Moussu was a Pendleton woman who had served in the Signal Corps during the war. Walsh's letter suggests the importance of networking among those Oregonians and Pendletonians serving abroad.

|

| "Miss Walsh in Serbia," Pendleton East Oregonian, May 1, 1920, 3. |

|

| "Pendleton Nurse in Poland Finds Much Poverty and Care," Pendleton East Oregonian, December 8, 1920, 1. |

Walsh was now in Red Cross service in Poland, again an independent country after World War I but where there was still conflict on its borders. Walsh gave information about where to send mail and information about her travels. And she gave a brief but informative description of her living quarters in the city of Kracow. "There is an immense castle just across the street from us. We are living in an old monastery. It is a find bring building but cold as a barn and no coal to heat it. We have one room with a storve and we sit there and write, and so forth, during the day."

Walsh's letter also reported on local and US women whom she had see and met in her travels to Paris, Belgrade, and Kracow. Several women were from California "and the western states" and "a number of them have been to the Pendleton Round-Up." Pendleton was becoming famous for its early fall Round-Up, ten years old in 1920. It became one common touchstone for Americans abroad who had visited Pendleton's attraction and a point of pride for Pendletonians abroad and at home.

Walsh also told her friend that she had seen Eglantine Moussu "in Paris several times." Moussu was a Pendleton woman who had served in the Signal Corps during the war. Walsh's letter suggests the importance of networking among those Oregonians and Pendletonians serving abroad.

|

| "Miss Eglantine Moussu," Pendleton East Oregonian, August 30, 1918, 1. |

Monday, July 27, 2015

Life After Base Hospital 46 Service in the First World War: Stasia Walsh Part II

As we saw in the last post, Base Hospital 46 nurse Stasia Walsh returned to Umatilla, Oregon after her wartime service and became involved in Red Cross community work, teaching classes in public health and home hygiene and helping victims of influenza.

She also identified herself as a veteran, a complicated thing for a woman following World War I.

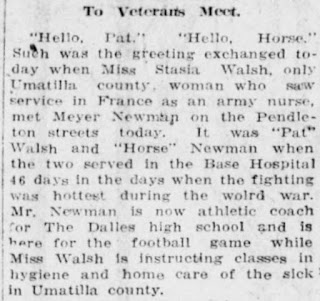

The Pendleton East Oregonian featured a brief account titled "T[w]o Veterans Meet" in October 1919 that presented Walsh as a veteran of the war.

In the account, Walsh met Meyer Newman "on the Pendleton streets" and they greeted one another with their nicknames from Base Hospital 46, she was "Pat" and he "Horse." Otis Wight's On Active Service with Base Hospital 46 lists Newman, from Corvallis, as a private serving as a guard in the Detachment Office and also the coach of the unit's football team. The newspaper account suggests that they were comrades in a powerful time "when the two served in the Base Hospital 46 days in the days when the fighting was hottest during the world war." They had also found a way to return to life in the States, he as high school athletic director at The Dalles and she in public health nursing in Umatilla County.

It is interesting to think about the implications of Walsh's decisions to identify as a veteran. Newspapers underscored her postwar professional life as stemming, in part, from her wartime service. Several of the articles I've posted here emphasized that Walsh was, as the article above stated, "the only Umatilla county woman who served in France as an Army nurse." And Walsh had lived through dangerous and difficult and sometimes enjoyable times in France as a member of Base Hospital 46, with male and female comrades. After the war women who had these experiences worked to be accepted as veterans, just as they had worked to be accepted in the male military.

Walsh had a new adventure on the horizon, as we'll see in the next post.

She also identified herself as a veteran, a complicated thing for a woman following World War I.

The Pendleton East Oregonian featured a brief account titled "T[w]o Veterans Meet" in October 1919 that presented Walsh as a veteran of the war.

|

| "T[w]o Veterans Meet," Pendleton East Oregonian, October 25, 1919, 1. |

|

| "[I]s Member of Legion," Pendleton East Oregonian, January 12, 1920, 6. |

In January 1920 the East Oregonian noted that Walsh had decided to join the veteran group the American Legion as the only woman member of the Pendleton post. We don't have a record of her thoughts on this, but she did choose to join the primarily male American Legion during her time in Umatilla county. When women who served overseas in the First World War created a parallel organization, the Women's Overseas Service League, Walsh joined the Oregon branch by 1925 (see the WOSL's magazine Carry On, vol. 4, no. 1 (February 1925): 35.

It is interesting to think about the implications of Walsh's decisions to identify as a veteran. Newspapers underscored her postwar professional life as stemming, in part, from her wartime service. Several of the articles I've posted here emphasized that Walsh was, as the article above stated, "the only Umatilla county woman who served in France as an Army nurse." And Walsh had lived through dangerous and difficult and sometimes enjoyable times in France as a member of Base Hospital 46, with male and female comrades. After the war women who had these experiences worked to be accepted as veterans, just as they had worked to be accepted in the male military.

Walsh had a new adventure on the horizon, as we'll see in the next post.

Monday, July 20, 2015

Life After Base Hospital 46 Service in the First World War: Stasia Walsh Part I

Following the story of Base Hospital 46 Nurse Stasia Walsh, R.N. after her First World War service reveals many compelling things about nursing, war service, and postwar medical humanitarian work. Over the next several posts I'll explore these issues and others such as citizenship, naturalization, and wartime and postwar service and how the Pendleton, Oregon newspaper the East Oregonian chronicled this "hometown" woman's service.

The editors of the Pendleton East Oregonian reported her return on the front page of the July 1, 1919 edition, noting with evident pride that she was the only Pendleton woman to serve overseas with a hospital unit. Friends and colleagues from St. Anthony's Hospital greeted her. The paper noted that she had visited Italy and her home country Ireland before her return.

Most members of the Army Nurse Corps in the First World War were first Red Cross nurses who then entered the Army as reserve nurses through the Red Cross. Walsh maintained her connection with the Red Cross upon her return to Eastern Oregon. That September, the Red Cross appointed her as a lecturer to cover Umatilla County "on home hygiene and the care of the sick."

As the field of social work expanded, nurses were in high demand for work on the public health home front.

The East Oregonian described the lessons that Walsh taught to young women (high school students) and older women for home hygiene. The Red Cross built lesson content on the idea that scientific medical training would empower women to handle health care in their homes and communities, part of a public health revolution. But the lessons also reinforced the idea that women would primarily be operating as unpaid workers in the home. Interestingly, the lessons for the 1919-1920 year would be free. Students needed to invest one dollar for a textbook.

As a nurse working at Base Hospital 46 in France, Stasia Walsh did not contract influenza during the pandemic in the fall of 1918; she certainly dealt with patients and colleagues who had the disease. There were subsequent waves of influenza after the war, and Walsh and her Red Cross colleagues volunteered to assist Oregonians in Umatilla County who were suffering from influenza in January 1920. The Pendleton East Oregonian reported that Walsh went to the city of Hermiston, "where she will have charge of the Red Cross Relief Work in checking the epidemic." It's interesting to note that the Red Cross provided food trays to families affected by the epidemic, some hundred strong.

More on Stasia Walsh in the next post.

| ||

| "Miss Stasia Walsh Arrives Home Today," Pendleton East Oregonian, July 1, 1919, 1. |

Most members of the Army Nurse Corps in the First World War were first Red Cross nurses who then entered the Army as reserve nurses through the Red Cross. Walsh maintained her connection with the Red Cross upon her return to Eastern Oregon. That September, the Red Cross appointed her as a lecturer to cover Umatilla County "on home hygiene and the care of the sick."

|

| "Miss Stasia Walsh is Appointed by R.C.," Pendleton East Oregonian, September 27, 1919, 1. |

|

| "Several Classes May be Conducted Here in Home Hygiene Course," Pendleton East Oregonian, October 4, 1919, Sec. 2:7 |

|

| "Red Cross Workers Visit Ill in City and Help Nearby Towns," Pendleton East Oregonian, January 29, 1920, 1. |

More on Stasia Walsh in the next post.

Monday, July 13, 2015

Life After Base Hospital 46 Service in the First World War: Helen Krebs Boykin

Helen Krebs, R.N. expanded her First World War Base Hospital 46 service to postwar medical humanitarian nursing with the Red Cross in Eastern Europe. Her service demonstrates that rather than an "end" to the war, continuing conflicts and the creation of hundreds of thousands of refugees and orphans meant instead a "long war" of the twentieth century and beyond.

one of the seven nurses of Base Hospital 46 "borrowed" for service before the unit could be completed and ready to sail. The army assigned Krebs to service in the Presidio in San Francisco. She returned home with most of the rest of the Hospital 46 staff in the spring of 1919.

Newspaper coverage gives us some additional information about the rest of her story.

The Oregonian reported in February 1920 that the Red Cross had assigned Krebs to join a unit for service in Russia, which was in the midst of revolution and civil war. We also learn that Krebs worked with her brother-in-law, Dr. Dorwin L. Palmer [OHSU records confirm Dorwin, not Darwin), who had charge of X-ray or Roentgenology work for the unit.

Palmer was a 1915 graduate of the University of Oregon Medical Department and conducted graduate study in Roentgenology at Cornell.

Krebs returned from her service in October 1920, and reported on her work in Bialystok, Poland in an orphanage with 700 children. The city had been invaded by the Germans, was part of the independent Polish state, and invaded by the Soviet Union during the Polish-Soviet War in 1919-1920 after which the city returned to Polish hands. Krebs saw firsthand the problems for refugees and children, and she joined other Oregonians like Esther Lovejoy and Marian Cruikshank who were engaged in medical humanitarian work with the American Women's Hospitals in this period.

On August 6, 1922, the Oregonian reported that Krebs had married Herbert C. Boykin, an orchardist from Husum, Washington. Dr. Dorwin Palmer and his wife, Helen's sister, served a bridal dinner with friends at Portland's University Club. ("Society News," Oregonian, August 6, 1922, Section 3, p. 4).

one of the seven nurses of Base Hospital 46 "borrowed" for service before the unit could be completed and ready to sail. The army assigned Krebs to service in the Presidio in San Francisco. She returned home with most of the rest of the Hospital 46 staff in the spring of 1919.

Newspaper coverage gives us some additional information about the rest of her story.

|

| "Red Cross Nurse is Soon to Join Russian Unit," Oregonian, February 22, 1920, Sec. 1, p. 11. |

|

| Otis Wight et. al. on Active Service with Base Hospital 46 (1920): 20. |

|

| "War Blights Children," Oregonian, October 21, 1920, 9. |

Krebs returned from her service in October 1920, and reported on her work in Bialystok, Poland in an orphanage with 700 children. The city had been invaded by the Germans, was part of the independent Polish state, and invaded by the Soviet Union during the Polish-Soviet War in 1919-1920 after which the city returned to Polish hands. Krebs saw firsthand the problems for refugees and children, and she joined other Oregonians like Esther Lovejoy and Marian Cruikshank who were engaged in medical humanitarian work with the American Women's Hospitals in this period.

On August 6, 1922, the Oregonian reported that Krebs had married Herbert C. Boykin, an orchardist from Husum, Washington. Dr. Dorwin Palmer and his wife, Helen's sister, served a bridal dinner with friends at Portland's University Club. ("Society News," Oregonian, August 6, 1922, Section 3, p. 4).

Monday, July 6, 2015

Overseas Nurses Guests of Honor

Oregon Base Hospital 46 nurses were frustrated with their lack of rank in the U.S. military and their return from France in the spring of 1919 provided the context for them to raise concerns about the second-class status of women nurses in the military. But they also returned to a profession strengthened by women's wartime service and the growth of social work and public health.

These currents came together when the Oregon Graduate Nurses Association hosted a dinner on June 18, 1919 at Portland's Central Library to honor the women nurses who had served overseas during the conflict, including Base Hospital 46 staff members. According to the Oregonian, each was asked to "give a short account of her experiences."

Speakers emphasized the connections among nursing and social services and social work. Emma Grittinger, the former head of Portland's Visiting Nurse Association, spoke in her new job as director of the Bureau of Public Health Nursing for the Northwestern Division of the Red Cross.

I've noted in some of our previous posts that some Base Hospital 46 women explored careers after the war that encompassed social service work; in the next few posts we'll trace a few more of the women in their postwar careers.

These currents came together when the Oregon Graduate Nurses Association hosted a dinner on June 18, 1919 at Portland's Central Library to honor the women nurses who had served overseas during the conflict, including Base Hospital 46 staff members. According to the Oregonian, each was asked to "give a short account of her experiences."

|

| "Overseas Nurses Dined," Oregonian, June 20, 1919, 13. |

I've noted in some of our previous posts that some Base Hospital 46 women explored careers after the war that encompassed social service work; in the next few posts we'll trace a few more of the women in their postwar careers.

Monday, June 29, 2015

Without the Dignity of Rank and the Respect Which It Insures, They Have Both Individually and Collectively Been . . . Misprized and Professionally Thwarted"

As we've seen in the last several posts, Oregon Base Hospital 46 Nurses joined nurses across the nation in protesting their second class status in the U.S. military. They had no official rank in an institution that was based on rank. From 1918 - 1920 nurses and their allies, including supporters of woman suffrage, worked to achieve rank for nurses. By 1919 most supported a middle ground proposal of "relative rank" that would give nurses a sort of official status but without the same pay and benefits as male officers (See my Mobilizing Minerva, pp. 123-141 for a discussion of this process). Congress passed the Jones-Raker Bill with "relative rank" for nurses as part of an army reorganization plan, and President Warren Harding signed it into law on June 4, 1920.

Many Oregon nurses supported action on rank for military nurses. The Oregon State Graduate Nurses Association, established in 1904 as an advocacy organization for nurses in the state, had Oregon Senator George Chamberlain, a member of the U.S. Senate's committee on Military Affairs, present a statement of support for rank from the association to the senate in 1919.

Mary C. Campbell, R.N. of Milwaukie, Oregon, was secretary of the Oregon State Graduate Nurses' Association and presented the statement to Chamberlain, which read:

"Without the dignity of rank and its evidence of authority to give orders, the nurses have been forced throughout their service to see the efficiency of their professional labors impaired.

"Without the dignity of rank and the respect which it insures, they have both individually and collectively been personally discommoded, embarrassed, ignored and misprized and professionally thwarted.

"Hence, it is indeed to be hoped that the new congress will give this matter its specific attention and by the conferring of rank on nurses eliminate the causes of these unfortunate consequences."

The nurses chose strong language to emphasize the weight of the offenses and emphasized their claims to dignity and respect. We don't often use the term "misprized" today, but it means to hold in contempt, to despise. I have argued in Mobilizing Minerva that nurses worked for rank, in part, to address gender based hostility and discrimination in the wartime workplace. This statement by the Oregon State Graduate Nurses' Associaion certainly supports this idea. And we also know that rank, even full rank that came during World War II, did not resolve the problems of the military workplace. But it was an important part of women's claims to economic citizenship and access to military professionalism and service.

The graduate nurse association also threw a party for returning Base Hospital 46 nurses as we'll see in the next post.

Many Oregon nurses supported action on rank for military nurses. The Oregon State Graduate Nurses Association, established in 1904 as an advocacy organization for nurses in the state, had Oregon Senator George Chamberlain, a member of the U.S. Senate's committee on Military Affairs, present a statement of support for rank from the association to the senate in 1919.

|

| "Rank for Nurses Likely," Oregonian, May 23, 1919, 28. |

"Without the dignity of rank and its evidence of authority to give orders, the nurses have been forced throughout their service to see the efficiency of their professional labors impaired.

"Without the dignity of rank and the respect which it insures, they have both individually and collectively been personally discommoded, embarrassed, ignored and misprized and professionally thwarted.

"Hence, it is indeed to be hoped that the new congress will give this matter its specific attention and by the conferring of rank on nurses eliminate the causes of these unfortunate consequences."

The nurses chose strong language to emphasize the weight of the offenses and emphasized their claims to dignity and respect. We don't often use the term "misprized" today, but it means to hold in contempt, to despise. I have argued in Mobilizing Minerva that nurses worked for rank, in part, to address gender based hostility and discrimination in the wartime workplace. This statement by the Oregon State Graduate Nurses' Associaion certainly supports this idea. And we also know that rank, even full rank that came during World War II, did not resolve the problems of the military workplace. But it was an important part of women's claims to economic citizenship and access to military professionalism and service.

The graduate nurse association also threw a party for returning Base Hospital 46 nurses as we'll see in the next post.

Monday, June 22, 2015

Base Hospital 46 Women Come Home: "Nurses To File Protests"

As we've seen in the last two posts, Eleanor Donaldson, Acting Chief Nurse of Oregon's Base Hospital 46 in the spring of 1919, outlined nurses' poor treatment and second-class status in the military in "Our Trip Home." Newspaper coverage suggests that many of the Base Hospital 46 nurses agreed with her.

In "Nurses Come Unheralded," the Oregonian reported their "unannounced and unexpected" arrival on the evening of April 27, 1919. "No reception committee greeted the nurses when they arrived. Miss Emily Loveridge, superintendent of the Good Samaritan hospital, was at the station to offer temporary homes to any of the girls who had no friends here." Evidently Loveridge had some advance notice of their arrival. And it appears that most had made arrangements to meet with friends and family.

Five days later the Oregonian reported evidence of the discrimination the nurses experienced that echoed Eleanor Donaldson's "Our Trip Home" in specific detail, with anger and frustration apparent in the recounting. "They were treated like cattle on the transport which carried them across the Atlantic, being left to take the crumbs which fell from the officers' tables, according to some of their stories. Another complaint is that when they landed at New York they were left to make their own way up town, carrying their own luggage and equipment while officers on the boat were transferred to their hotels in taxis and limosines."

This report indicates that some other Base 46 nurses shared Donaldson's outrage and were determined to act. "A document of protest signed by many of the nurses is expected to reach the proper authorities in due course of time." But first, the women needed to leave the army to avoid negative consequences for the protest. As the Oregonian noted, "the sensation . . . will have to await the day when the nurses have shed their uniforms and are safely separated from the military establishment by official parchments acknowledging their faithful services and their honorable discharges." Like other nurses' stories of protest I covered in Mobilizing Minerva, they waited until the military could not retaliate against them as individuals.

At present I don't have a record of any "document of protest". But many nurses and their allies worked for rank for military nurses as a way to resolve what Eleanor Donaldson noted as a key lesson she learned: "a nurse has no standing in the army."

|

| "Nurses Come Unheralded," Oregonian, April 28, 1919, 7. |

|

| "Nurses to File Protests," Oregonian, May 3, 1919, 4. |

This report indicates that some other Base 46 nurses shared Donaldson's outrage and were determined to act. "A document of protest signed by many of the nurses is expected to reach the proper authorities in due course of time." But first, the women needed to leave the army to avoid negative consequences for the protest. As the Oregonian noted, "the sensation . . . will have to await the day when the nurses have shed their uniforms and are safely separated from the military establishment by official parchments acknowledging their faithful services and their honorable discharges." Like other nurses' stories of protest I covered in Mobilizing Minerva, they waited until the military could not retaliate against them as individuals.

At present I don't have a record of any "document of protest". But many nurses and their allies worked for rank for military nurses as a way to resolve what Eleanor Donaldson noted as a key lesson she learned: "a nurse has no standing in the army."

Monday, June 15, 2015

Eleanor Donaldson and "Our Trip Home" Part II: "And This is How B.H. 46 Came Home"

The last post focused on Base Hospital 46 Acting Chief Nurse Eleanor Donaldson's critique of U.S. Army policy and practice toward members of the Army Nurse Corps on their journey back home to the States from France. Here is the rest of her description and challenge to the discrimination she felt in the last section of "Our Trip Home".

Donaldson also complained that she and her staff had tried to comply with Army Nurse Corps orders to "pack our few un-military belongings." But they were "in the minority. Gay sweaters, jeweled hands and civilian one-piece dresses were the rule even with some of the chief nurses. The nurses in charge resigned themselves to the inevitable and asked only that we wear strict uniform when leaving the boat." Donaldson evidently felt that preserving military dress and decorum would be the best way for nurses to return home safely and responsibly, and was angry that this didn't happen.

There was, in Donaldson's mind, a final indignity and double standard for male officers and nurses. "We were nine days crossing; on the morning of the tenth day we disembarked. Ambulances were in readiness for their officers and their hand bags. After waiting an hour we were asked to walk to the Polyclinic. It was not a long walk and we wouldn't have cared, only we did a little. And this is how B.H. 46 came home."

How did other Base Hospital 46 nurses react? More in the next post.

Donaldson also complained that she and her staff had tried to comply with Army Nurse Corps orders to "pack our few un-military belongings." But they were "in the minority. Gay sweaters, jeweled hands and civilian one-piece dresses were the rule even with some of the chief nurses. The nurses in charge resigned themselves to the inevitable and asked only that we wear strict uniform when leaving the boat." Donaldson evidently felt that preserving military dress and decorum would be the best way for nurses to return home safely and responsibly, and was angry that this didn't happen.

There was, in Donaldson's mind, a final indignity and double standard for male officers and nurses. "We were nine days crossing; on the morning of the tenth day we disembarked. Ambulances were in readiness for their officers and their hand bags. After waiting an hour we were asked to walk to the Polyclinic. It was not a long walk and we wouldn't have cared, only we did a little. And this is how B.H. 46 came home."

How did other Base Hospital 46 nurses react? More in the next post.

Monday, June 8, 2015

Eleanor Donaldson and "Our Trip Home" Part I: Nurses "Felt the Injustice Keenly"

Base Hospital 46 Nurse Eleanor Donaldson became Acting Chief Nurse for the hospital unit during the months of demobilization and return to the States in the spring of 1919. Donaldson authored a two page account titled "Our Trip Home" found in Record Group 112, Army Nurse Corps Historical Data File 1898-1947 at the U.S. National Archives. Her frustration with the way that Base Hospital 46 nurses were treated shouts through every paragraph. Because military nurses had no official rank, such frustrations became active calls for rank for Army nurses [Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008).] I'll cover the Base Hospital 46 nurses' part in that process in a later post.

|

| Donaldson, "Our Trip Home". |

"At first we thought a mistake had been made, so terribly dirty and unprepared were our quarters. The ship . . . had been rented from the Germans and delivered only six days before. The "dough boys" [U.S. soldiers] were working twenty hours out of the twenty four to put it in shape. The officers quarters and those of the non commissioned officers were in order. Our quarters were decks down and in the sick room were unswept the waste water of the former occupant still in their recepticles [sic]. Fortunately the notices for venereal diseases only were still posted in bath and toilet, one of the chief nurses sent to Brest for lysol and took personal charge of the cleaning."

Donaldson was appalled at the dirty conditions but was particularly galled at the double standard of the quarters for nurses versus those of the men.

"Major W.H. Skene," the Base Hospital 46 doctor, she continued, was "still in the belief that it was a mkstake and not of Uncle Sams. . . . Some of us protested to those in command and were promptly told that this was military law, nurses had no standing in the army and etc. It was some time before we accepted our fate, although we set to work at once to clean things up. These girls who had worked gladly and uncomplainingly and without adequate rest, when the work was required felt the injustice keenly, they still do."

More from Donaldson's indictment of military policy and practice in "Our Trip Home" in the next post.

Monday, June 1, 2015

The Women Civilian Employees of Base Hospital 46 Part II: Stenographers LaVina McKeown, M. Ethel Gulling, and Jennie Davis

Three women served as stenographers to support the burgeoning paperwork and bureaucracy of the First World War military for Oregon's Base Hospital 46 in France. They were experienced in office management and stenography and, like the laboratory assistants and dietitian of the unit, were civilian employees under contract with the United States Army.

Jennie Davis, for whom we don't have a file, trained at the Bean's School of Shorthand in Portland, Maine (Wight, On Active Service With Base Hospital 46, p. 26).

Jennie Davis, for whom we don't have a file, trained at the Bean's School of Shorthand in Portland, Maine (Wight, On Active Service With Base Hospital 46, p. 26).

Monday, May 25, 2015

The Women Civilian Employees of Base Hospital 46 Part I: Agatha Holloway and Vida Fatland, Laboratory Assistants, and Gertrude Palmer, Dietician

There were six women who served with Oregon's Base Hospital 46 in France during the First World War who were not nurses. In this post I'll introduce the three who had scientific technical training: Agatha Holloway and Vida Fatland, who served as laboratory assistants and Gertrude Palmer, who was the unit's dietician. They were civilian employees whose work was vital to the unit but who worked under contract rather than with in the military.

Vida Fatland, whose image was not included in Phelps's file, was a 1915 biology graduate from Reed College in Portland.

Vida Fatland, whose image was not included in Phelps's file, was a 1915 biology graduate from Reed College in Portland.

Monday, May 18, 2015

Nurse Marian Brehaut at Base Hospital 46: "We May Get Home for Christmas Dinner Yet"

With the approach of the November 11, 1918 Armistice and the passing of the worst of the influenza epidemic, staff at Base Hospital 46 continued their work but hoped for a return home by the winter holidays. The Oregon Journal published excerpts from Unit 46 nurse Marian Brehaut's letter home, apparently written just before the Armistice. Her letter reflects both the continuing work with wounded men and the hope of returning home. She gives details of what it was like to be on night duty in the face of air raids.

Marian Brehaut, who trained at Winnepeg General Hospital Training School for Nurses, wrote to her sister, Mrs. David Pattullo in Portland:

"Our hospital is full. As soon as the wounded men are able to be moved we ship them south and get new patients, some of whom are fresh from the battlefield, that is they have only been at the field dressing station before they come to us. Frequently we have them for only a day or two, when they are evacuated to make room for newly wounded men. A convoy came in tonight bringing men with the worst wounds we have yet had. It seems so barbarous to have these fine chaps all cut to pieces.

"The news looks extremely good and, if it is true, we may get home for Christmas dinner yet. The medical corps, as you know, is the last to leave the field.

"I am on night duty for the next two weeks. Night work is as hard as day duty in camp hospitals. We have been furnished stoves so we can keep warm. After the lights go out we can use coal oil lamps or lanterns except when there is an air raid, when, of course, we must extinguish all the lights. You can imagine what it means to take care of 50 patients in the dark. On rainy nights we are never troubled with air raids. The Germans prefer the bright moonlight nights.

"One of the boys of our unit, Dr. Coffey's son, has gone home on account of poor health. You will probably see him. You can ask him any questions you want to know about our work over here.

"We have had a lot of Oregon boys lately. Their division was pretty well shot to pieces, we hear, but you of course will have the word sooner than this.

"It rains about five days a week--very much like Oregon fall only colder.

"The best things the Red Cross gave us were our sleeping bags, which are wooly and warm. We night nurses sleep out in a tent. It is quiet out there and we all enjoy it."

| ||

| "Portland Nurse Writes of Duties in Camp Hospital," Oregon Journal, November 25, 1918, 3. |

"Our hospital is full. As soon as the wounded men are able to be moved we ship them south and get new patients, some of whom are fresh from the battlefield, that is they have only been at the field dressing station before they come to us. Frequently we have them for only a day or two, when they are evacuated to make room for newly wounded men. A convoy came in tonight bringing men with the worst wounds we have yet had. It seems so barbarous to have these fine chaps all cut to pieces.

"The news looks extremely good and, if it is true, we may get home for Christmas dinner yet. The medical corps, as you know, is the last to leave the field.

"I am on night duty for the next two weeks. Night work is as hard as day duty in camp hospitals. We have been furnished stoves so we can keep warm. After the lights go out we can use coal oil lamps or lanterns except when there is an air raid, when, of course, we must extinguish all the lights. You can imagine what it means to take care of 50 patients in the dark. On rainy nights we are never troubled with air raids. The Germans prefer the bright moonlight nights.

"One of the boys of our unit, Dr. Coffey's son, has gone home on account of poor health. You will probably see him. You can ask him any questions you want to know about our work over here.

"We have had a lot of Oregon boys lately. Their division was pretty well shot to pieces, we hear, but you of course will have the word sooner than this.

"It rains about five days a week--very much like Oregon fall only colder.

"The best things the Red Cross gave us were our sleeping bags, which are wooly and warm. We night nurses sleep out in a tent. It is quiet out there and we all enjoy it."

Thursday, May 14, 2015

Bringing Home Bodies After World War I: The Case of Norene Royer

There was one death among the women of Base Hospital 46 in France during World War I. I've been posting information about the death of nurse Norene Royer and suggesting that the information about her death can tell us a great deal about the experience women and World War I.

The staff of Base Hospital 46 in Bazoiilles-sur-Meuse France held a funeral for and buried Royer's body on September 18, 1918. But like many family members of those who died in World War I, her family wanted to have her body returned and repatriated to the United States.

Lisa Budreau, author of Bodies of War: World War I and the Politics of Commemoration in America, 1919-1933 (New York University Press, 2011) notes that the return of the American war dead was "disorganized" and "unplanned for." Problems of transportation, labor, and mismanagement were the rule. Budreau notes that by "the close of 1921, the gruesome burial work was nearly complete after the American military had shipped close to 46,000 dead to the United States."

The army shipped Royer's body home in June, 1921, first to Portland and then to her home in Spokane.

The Oregonian noted that Stella Brown would represent Base Hospital 46 at this reburial.

The staff of Base Hospital 46 in Bazoiilles-sur-Meuse France held a funeral for and buried Royer's body on September 18, 1918. But like many family members of those who died in World War I, her family wanted to have her body returned and repatriated to the United States.

Lisa Budreau, author of Bodies of War: World War I and the Politics of Commemoration in America, 1919-1933 (New York University Press, 2011) notes that the return of the American war dead was "disorganized" and "unplanned for." Problems of transportation, labor, and mismanagement were the rule. Budreau notes that by "the close of 1921, the gruesome burial work was nearly complete after the American military had shipped close to 46,000 dead to the United States."

The army shipped Royer's body home in June, 1921, first to Portland and then to her home in Spokane.

|

| "Nurse's Body Due Today," Oregonian, June 2, 1921, 7. |

Frances Estella Browne, Grace Phelps Papers, Box 3, Binder 5, Base Hospital 46 Staff

Files, Historical Collections & Archives, Oregon Health & Science

University. Courtesy Historical Collections &Archives, OHSU.

Frances Estella Brown, R.N. was from Fossil, Oregon and trained at the Good Samaritan Hospital Training School for nurses. That the represented Base Hospital 46 at Royer's reburial in Spokane suggests suggesting a strong and continuing group identity for many of the women of the unit after the war.

Monday, May 11, 2015

Deaths in the Army Nurse Corps During World War I

I've been posting material about Norene Royer, a member of the Army Nurse Corps and staff of Oregon's Base Hospital 46 in Bazoilles-sur-Meuse, France. Royer was the only female staff member who died during the conflict. How did this compare with the Army Nurse Corps in general?

In November 1918 there were 21, 480 nurses in the Army Nurse Corps, with over 10,000 serving with the American Expeditionary Force in France. (Julia Stimson, "The Army Nurse Corps," Part Two of Volume 13 The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1927), 290.) Stimson's records showed 134 deaths in the nurse corps in the United states, primarily from influenza. One hundred two women serving with the American Expeditionary Force died in service from 1917 to 1919. Norene Royer was among those who died due to the influenza epidemic (Stimson, 350).

The women's veteran organization the Women's Overseas Service League had a record of six women in the Northwest who died serving outside the U.S. in the World War. They listed Norene Royer at the address of her sister in Winchester, Idaho. And they also named Ima L. Ledford of Hillsboro. Ledford served with the Army Nurse Corps at Base Hospital 116, also at Bazoilles-sur-Meuse. She died on October 7, 1918. [Lavinia Dock, et al., History of American Red

Cross Nursing (New York: MacMillan, 1922), 1482.]

In November 1918 there were 21, 480 nurses in the Army Nurse Corps, with over 10,000 serving with the American Expeditionary Force in France. (Julia Stimson, "The Army Nurse Corps," Part Two of Volume 13 The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1927), 290.) Stimson's records showed 134 deaths in the nurse corps in the United states, primarily from influenza. One hundred two women serving with the American Expeditionary Force died in service from 1917 to 1919. Norene Royer was among those who died due to the influenza epidemic (Stimson, 350).

|

| "Gold Star Women 161," Oregonian, November 12, 1922, Sec. 1, 1. |

Thursday, May 7, 2015

Norene Royer's Personal Effects in September 1918: "1 Cap, boudoir . . .1 Belt, money . . . 4 Stockings, pairs, 1 Diary"

In addition to the official papers Norene Royer left behind at her death, materials in the Grace Phelps Papers at the Historical Collections & Archives at the Oregon Health & Science University tell us just what Royer had with her when she died. This provides another window onto life for the women of Base Hospital 46 in France in World War I.

In the certified copy listing Royer's effects Chief Nurse Grace Phelps gave to Quartermaster Malcolm Black, we find some of the specific items that made up her life and work. Some of the items seem very familiar to travelers today -- a money belt, pajamas, a traveling case for toiletries. Other clothes and effects, like the boudoir cap, seem very far away from us.

1 Cap, Boudoir

1 Mirror

1 Stamping Set [presumably for letter writing]

1 Scissors, pair

3 Collars

1 Box Writing Paper

2 Flash lights

2 Hangers

2 Combinations, wool

1 Belt, money

1 Skirt, blue

5 Teddies

1 Shoes, pair

2 Skirts, white

4 Corsets

1 Basket (2 books enclosed)

4 Towels

1 Apron, large

4 Stockings, pairs

2 hypo sets

1 Toilet traveling case

1 Diary

1 Box letters

1 Manicure set

1 Bag, laundry

5 pajamas, pairs

2 Towels, hand

2 Waists, silk, blue

2 Kimonos

1 Uniform, White

1 Skirt, satin

9 Brassieres

3 cloths, wash

5 vests

Thinking about this list of Norene Royer's effects underscores the challenges nurses had with laundry and makes me hope that someone still has the diary that was, presumably, sent to her mother. I would love to know the titles of the two books in the basket and have the chance to read the letters in her box.

| |

| "Norene Royer," Box 1, Folder 8, Grace Phelps Papers, Historical Collections & Archives, Oregon Health & Science University. Courtesy Historical Collections & Archives, OHSU. |

1 Cap, Boudoir

|

| Crocheted Boudoir Cap, Royal Society Crochet Lessons (New York: H.E. Verran, 1917), 2. |

1 Mirror

1 Stamping Set [presumably for letter writing]

1 Scissors, pair

3 Collars

1 Box Writing Paper

2 Flash lights

|

| Niagara Flashlight, 1918, Flashlight Museum |

2 Combinations, wool

1 Belt, money

1 Skirt, blue

5 Teddies

1 Shoes, pair

2 Skirts, white

4 Corsets

1 Basket (2 books enclosed)

4 Towels

1 Apron, large

4 Stockings, pairs

2 hypo sets

1 Toilet traveling case

|

| This traveling case on the left was for the "soldier or traveler" but may have resembled Norene Royer's toilet traveling case. Oregonian, June 19, 1918, Section 5, p. 7. |

1 Box letters

1 Manicure set

1 Bag, laundry

5 pajamas, pairs

2 Towels, hand

2 Waists, silk, blue

2 Kimonos

1 Uniform, White

|

| World War I Nurse's Uniform, National Archives. |

9 Brassieres

3 cloths, wash

5 vests

Thinking about this list of Norene Royer's effects underscores the challenges nurses had with laundry and makes me hope that someone still has the diary that was, presumably, sent to her mother. I would love to know the titles of the two books in the basket and have the chance to read the letters in her box.

Monday, May 4, 2015

Identity Papers and Paperwork for Norene Royer at her Death

The last post noted that Base Hospital 46 Chief Nurse Grace Phelps sought guidance about how to deal with the possessions of nurse Norene Royer at her death in September 1918. Materials in the Grace Phelps Papers at the Historical Collections

& Archives at the Oregon Health & Science University help us learn more about that process and also provide information about the effects of one woman in service with the Army Nurse Corps in World War I.

Phelps had to turn over Royer's military and employment papers and what were considered her valuables to Quartermaster Malcolm S. Black of Base Hospital 46. Royer, and presumably all base hospital nurses in France, had three separate papers or cards that they were required to have with them. One was her Appointment Card, the second was her Certificate of Identity, and the third was her Workers' Permit. She also had a purse with her watch and 285 francs inside it. Phelps described the purse as a "pocketbook with [Royer's] name on it." (Memorandum - Special, Base Hospital 46, Office of Chief Nurse, September 20, 1918, Box 1, Folder 7, Grace Phelps Papers, Historical Collections & Archives at the Oregon Health & Science University.)

A look at the personnel of the Quartermaster Department at Base Hospital 46 suggests varied duties for the staff in this department that related directly to keeping the unit running.

In addition to those who worked at headquarters processing staff paperwork and working with supplies, four men were detailed to deal with patients' clothing, two were plumbers, and eight were carpenters.

Phelps had to turn over Royer's military and employment papers and what were considered her valuables to Quartermaster Malcolm S. Black of Base Hospital 46. Royer, and presumably all base hospital nurses in France, had three separate papers or cards that they were required to have with them. One was her Appointment Card, the second was her Certificate of Identity, and the third was her Workers' Permit. She also had a purse with her watch and 285 francs inside it. Phelps described the purse as a "pocketbook with [Royer's] name on it." (Memorandum - Special, Base Hospital 46, Office of Chief Nurse, September 20, 1918, Box 1, Folder 7, Grace Phelps Papers, Historical Collections & Archives at the Oregon Health & Science University.)

A look at the personnel of the Quartermaster Department at Base Hospital 46 suggests varied duties for the staff in this department that related directly to keeping the unit running.

|

| Wight et al. On Active Service with Base Hospital 46, 39. |

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Julia Stimson to Grace Phelps: "I Can Imagine Nothing Worse For a Chief Nurse Than the Death of One of Her Staff"

Materials relating to the September 1918 death of Base Hospital 46 nurse Norene Royer in the Grace Phelps Papers at the Historical Collections & Archives at the Oregon Health & Science University reveal a great deal about Rogers and expand our understanding of life for women on staff with the unit.

Chief nurse Grace Phelps received a letter from Julia Stimson, then the chief nurse of the American Red Cross in France, and soon to be the chief nurse of the American Expeditionary Force. The letter reveals some of the concerns chief nurses experienced, and also details about what Phelps should do with Royer's effects. It appears that Stimson wrote the letter in response to one from Phelps informing her of Royer's death. [For more on Stimson, see Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 136-141]

"I am so sorry you have been through such a trying time," Stimson wrote to Phelps on September 30, almost two weeks after Royer's death. "I can imagine nothing worse for a Chief Nurse than the death of one of her staff, for not only is it often a personal loss, but the effect upon the whole group of nurses is so great, that the burden of the Chief Nurse is increased by the necessary efforts she must make to counteract and relieve the depression of the whole group. You have my deepest sympathy." (Julia Stimson to Grace Phelps, September 30, 1918, Box 1, Folder 7, Grace Phelps Papers, Historical Collections & Archives, Oregon Health & Science University).

Stimson and Phelps took their leadership positions seriously and felt responsible for the nurses under their direction. Their writings and papers also suggest that both felt that nursing was on the world stage as a result of the war and wanted to make a strong showing for women's professionalism in wartime medicine.

Phelps had apparently written Stimson to ask what she should do with the equipment the Red Cross/Army Nurse Corps had issued to Royer. "Use Miss Roger's [sic] equipment as you think best. The only times when we want Red Cross equipment returned to us are on those occasions when its return is necessary in order to prevent the unworthy or unauthorized use of it." Stimson's comments suggest the pride with which she viewed the uniform and equipment of wartime nursing and also the logistical challenges of returning things from the war zone.

Chief nurse Grace Phelps received a letter from Julia Stimson, then the chief nurse of the American Red Cross in France, and soon to be the chief nurse of the American Expeditionary Force. The letter reveals some of the concerns chief nurses experienced, and also details about what Phelps should do with Royer's effects. It appears that Stimson wrote the letter in response to one from Phelps informing her of Royer's death. [For more on Stimson, see Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 136-141]

|

| Julia Stimson, ca. 1919, Library of Congress. |

Stimson and Phelps took their leadership positions seriously and felt responsible for the nurses under their direction. Their writings and papers also suggest that both felt that nursing was on the world stage as a result of the war and wanted to make a strong showing for women's professionalism in wartime medicine.

Phelps had apparently written Stimson to ask what she should do with the equipment the Red Cross/Army Nurse Corps had issued to Royer. "Use Miss Roger's [sic] equipment as you think best. The only times when we want Red Cross equipment returned to us are on those occasions when its return is necessary in order to prevent the unworthy or unauthorized use of it." Stimson's comments suggest the pride with which she viewed the uniform and equipment of wartime nursing and also the logistical challenges of returning things from the war zone.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)